anachek -

introduction

anachek is the most widely spoken language on notasami, and the second largest language by number of native speakers, before tangachi. it originated from the xesfaran plateau in gutonim.

classification

anachek is a member of the xesfaran language family, related to bulensunas and more distantly qodoyinas. anachek is a member of a dialect continuum including jompalinas and rezirenas, sometimes considered separate languages and sometimes not. externally, the xesfaran languages may either be distantly related to or had been in a sprachbund with ancient xesfaran, namak, koposem, and perhaps farxariman.

history

proto-xesfaran is thought to have been spoken around the western edge of the xesfaran plateau up to around -2000, after which splitting into lacustrine xesfaran to the east, around the lakes of the xesfaran plateau, and riverine xesfaran to the west, which is thought to have been the language of the kuzagrēo and the ancestor of qodoyinas.

speakers of lacustrine xesfaran are then thought to have migrated to the coast during the collapse of the dalassan empire in 200, fully supplanting ancient xesfaran and soon after splitting into low and high xesfaran. low xesfaran would evolve into bulensunas to the north, and high xesfaran would then give rise to anachek.

high xesfaran soon became a dominant language in the area, initially often competing with low xesfaran. as such, it was not influenced very heavily by other languages, rather it was, and still is to this day, the one influencing other languages. in spite of this, anachek still contains many loanwords from namak and farxariman, often in scientific and higher class registers.

its current status as a globally dominant language originates from the colonial empire of gutonim spreading the language throughout its colonies around the world.

phonology

consonants

| labial | dental | palatal | velar | glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | voiced | b [b] | d [d] | j [dʒ] | g [g] | |

| unvoiced | p [p] | t [t] | c [tʃ] | k [k] | q [ʔ] | |

| fricative | voiced | v [v] | z [z] | |||

| unvoiced | f [f] | s [s] | š [ʃ] | x [x] | h [h] | |

| nasal | m [m] | n [n] | ||||

| flap | r [ɾ] | |||||

| approximants | w [w] | l [l] | y [j] | |||

at the end of a word, the stop consonants /p, b, t, d, k, g/ are unreleased.

before the vowel /i/, the stops /t d/ are slightly fricated [tˢ dᶻ].

the affricates /tʃ dʒ/ are pronounced [ts dz] in some dialects, particularly in western gutonim.

/ʃ/ is voiced [ʒ] intervocalically in some dialects, including across word boundaries, particularly in eastern gutonim and northern beniras.

/x/ is often uvular [χ].

/h/ is often voiced [ɦ] between vowels, including across word boundaries.

/r/ is in free variation between a tap [ɾ] and a trill [r].

/w/ is delabialised [ɰ] in dialects of western gutonim; an areal feature shared by jompalinas, qodoyinas, northern dialects of fetgalana, and some northern namak languages.

vowels

| front | back | |

|---|---|---|

| close | i [i] | u [u] |

| mid | e [e] | o [o] |

| open | a [ɐ] | |

the vowels /e o/ are commonly lowered [ɛ ɔ] in unstressed syllables.

vowels are frequently nasalised when surrounded by nasal consonants /m n/.

stress

stress in anachek is consistently word-initial. secondary stress falls on the last syllable in tri-syllabic words, and on the penultimate syllable in words of four or more syllables, alternating back to the left edge.

phonotactics

the maximal syllable in anachek is CVC; that is, clusters can only happen cross-syllabically. loanwords that violate this pattern often employs echo vowels to rectify invalid syllables:

while phonetically nuclei group with onsets rather than codas CV-C; because of the writing system, conscious syllabification is done in terms of onsets and rimes C-VC.

long vowels are not allowed.

writing

anachek has two official writing systems; pureda mufena and pureda far, heavy alphabet and light alphabet

pureda mufena, also known as the anachek syllabary, is the main form of writing. it is referred to as the heavy alphabet in reference to its relatively higher amount of phonemes per grapheme than the widespread namak script, the former being a syllabary and the latter an alphabet.

pureda far is the transliteration of anachek into the namak script, the most widely used writing system on notasami.

pureda mufena / syllabary

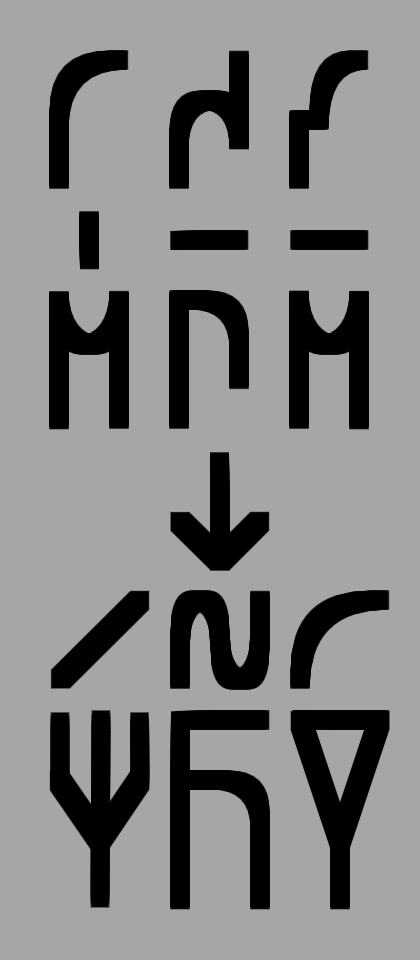

syllabic waptokan (top)

versus anachek (bottom)

the anachek syllabary is unusual for representing rimes in its base graphemes instead of onset-nucleus pairs like typical syllabaries. this originates from a specific style of writing in the waptokan script, where syllables were grouped by being written vertically with the rest of the word and sentence still written left to right. the bottom two characters, the nucleus and the coda, ended up merging into a single character, forming a syllabary, leaving the onset as a separate diacritic above.

| -C | C- | a [ɐ] | u [u] | e [e] | o [o] | i [i] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p [p] | p- | ap | up | ep | op | ip |

| r [ɾ] | r- | ar | ur | er | or | ir |

| d [d] | d- | ad | ud | ed | od | id |

| s [s] | s- | as | us | es | os | is |

| š [ʃ] | š- | aš | uš | eš | oš | iš |

| c [tʃ] | c- | ac | uc | ec | oc | ic |

| t [t] | t- | at | ut | et | ot | it |

| x [x] | x- | ax | ux | ex | ox | ix |

| k [k] | k- | ak | uk | ek | ok | ik |

| l [l] | l- | al | ul | el | ol | il |

| g [g] | g- | ag | ug | eg | og | ig |

| z [z] | z- | az | uz | ez | oz | iz |

| j [dʒ] | j- | aj | uj | ej | oj | ij |

| f [f] | f- | af | uf | ef | of | if |

| b [b] | b- | ab | ub | eb | ob | ib |

| v [v] | v- | av | uv | ev | ov | iv |

| m [m] | m- | am | um | em | om | im |

| w [w] | w- | aw | uw | ew | ow | iw |

| h [h] | h- | ah | uh | eh | oh | ih |

| n [n] | n- | an | un | en | on | in |

| y [j] | y- | ay | uy | ey | oy | iy |

| q [ʔ] | q- | aq | uq | eq | oq | iq |

| ∅ | -- | a | u | e | o | i |

pureda far / namakisation

the following is the transcription of anachek into the namak alphabet.

| namak | Pp | Rr | Dd | Ss | Šš | Cc | Tt | Xx | Ll | Gg | Zz | Jj | Ff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ipa | /p/ | /r/ | /d/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /tʃ/ | /t/ | /x/ | /l/ | /g/ | /z/ | /dʒ/ | /f/ |

| latin | p | r | d | s | š | c | t | x | l | g | z | j | f |

| namak | Bb | Vv | Aa | Mm | Uu | Ùù | Ee | Oo | Hh | Nn | Ii | Ìì | Ĝĝ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ipa | /b/ | /v/ | /ɐ/ | /m/ | /u/ | /w/ | /e/ | /o/ | /h/ | /n/ | /i/ | /j/ | /ʔ/ |

| latin | b | v | a | m | u | w | e | o | h | n | i | j | q |

derivational morphology

to nouns

adjectives can naturally be interchangable with nouns, typically an abstract noun describing that quality.

it is important to note that this is ambiguous with a headless noun phrase

verbs can become an abstract noun with the prefix ho-.

verbs can form agent nouns with the suffix -u.

to verbs

nouns and adjectives can recieve the standard causative suffix -uxu to form causative verbs.

to adjectives

verbs can be made into adjectives with the suffix -ni.

nouns can be made into adjectives with the suffix -axi.

other

ordinal numbers are formed with the prefix ka-. this precludes the number 1 whose ordinal form is tape, borrowed from namak.

diminutives are formed with the suffix -ak.

augmentatives are formed with the suffix -yu.

nouns

noun phrase order

the overall order of the constituents of a noun phrase is:

- determiners: articles, demonstratives, possessives, quantifiers

- nouns: number-stem-case

- numbers

- genitives

- adjectives: number-stem-gender

- prep. phrases:

- other

- locative

- temporal

nounless noun phrases

sometimes noun phrases can be headed by words other than nouns such as adjectives in cases where it would modify a noun that is unimportant or understandable in context, corresponding to the english construction "[adj] one":

with adjectives this can be ambiguous with their nominalised forms, but this is usually distinguishable by context

this does not apply to possessive pronouns or demonstratives, however; possessives must take bet "one" as a head noun, and demonstrative adverbs must take some appropriate noun, excluding the core demonstratives which have pronominal forms.

determiners

anachek has a definite article ji and no indefinite article. nouns standing for general concepts do not take an article.

the definite article is not added if the noun is modified by a possessive or a demonstrative.

anachek also distinguishes between pronominal demonstratives and adjectival demonstratives, both having a two-way distance distinction. both must also agree in number and gender with their referent, but not in case. the following are the adjectival demonstratives:

| number/space | class I | class II |

|---|---|---|

| S.proximal | fi |

fe |

| S.distal | rar |

yur |

| P.proximal | ra |

gu |

| P.distal | nik |

nuk |

number

most nouns are inherently singular, and with the prefix gu- can be marked as plural.

adjectives have to agree in number with the noun they modify. they take the same plural marker.

case

nouns can take one of five cases, besides the default bare form.

the genitive case is marked with the suffix -nas. this is used on nouns so they can act as modifiers to other nouns. it is also used to show possession, which will be discussed in the next section. genitive nouns do not have to match with their head's gender.

the ablative case can be marked with -ka. this case is used to mark a noun as the origin location for some other noun it modifies. it has also been metaphorically extended to show a causal case; that is, indicating that the noun is the cause for something.

the locative case is shown using the suffix -pal. this case is always used when a noun occurs in conjunction with a preposition. a noun with the locative case without a head preposition defaults to a general "in" or "at" meaning.

it is important to note that, unless specifying a particular direction with a preposition, semantically locative objects of locomotive verbs do not take the locative case.

the instrumental case is marked with -ruy. this is used to indicate that a noun was the instrument with which something happened. it is also used when one wants to explicitly indicate the topic of a clause.

the vocative case can be shown with -yun. this case is used to address a particular noun, often proper nouns. it is somewhat rare, occuring mostly only formally and dialectically, and even still it is usually used to show emphasis.

possession

possession is indicated between two nouns using the genitive case as stated above. otherwise, the genitive set of pronouns can be used, placed before the possessee.

gender

nouns can be grouped into two formal genders based on the last vowel in the stem, called classes. class I nouns have a or i as their final vowel, while class II nouns' final vowels are u, o, or e. there is no obvious semantic patterning to the assignment of nouns to classes; older literature calls class I 'masculine' and class II 'feminine' but this terminology is not preferred as there are no productive semantic associations between the classes.

gender is only relevant in the case of adjectives. adjectives are also categorised into the two classes in the same way nouns are, and when assigned to a noun they must also agree with the noun's gender. if the adjective's inherent gender does not match the noun's, the following two suffixes are used: -(n)a can switch a class II adjective to class I, and -(g)u can switch a class I adjective to class II.

pronouns

the following table shows the personal pronouns in anachek, which agree in number and case, but not gender:

| person | nominative | accusative | genitive | dative | ablative | instrumental |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1S | ben |

ber |

benas |

benal |

bena |

benuy |

| 2S | ran |

bor |

bas |

bal |

burka |

buy |

| 3S | nan |

nir |

nunas |

nunal |

nuna |

nuy |

| 1P | bun |

ber |

benus |

benul |

benu |

benur |

| 2P | run |

bur |

rus |

rul |

burku |

rur |

| 3P | nun |

nur |

nus |

nul |

nunu |

nunur |

pronouns can be dropped if the information they stand for is already shown eg. through a verb.

this also happens if the verb is a simple verb and is not encoding any person/number information, if it is obvious the subject pronoun can still be dropped here, though only in informal speech.

a pronoun can also be used to show emphasis by being placed redundantly after a noun and agreeing with it.

the following table shows the pronominal demonstratives, which agree in number and gender, but not case:

| number/space | class I | class II |

|---|---|---|

| S.proximal | ris |

rus |

| S.distal | pan |

bun |

| P.proximal | kas |

gus |

| P.distal | tan |

fun |

when pronominal demonstratives do not explicitly point back to a referent, the class II form is used, to hypothetically agree with the word muned 'thing'.

the following are the interrogative pronouns, mainly used in questions:

| pronoun | usage | translation |

|---|---|---|

rik |

class I | who/what/which |

rek |

class II | who/what/which |

gut |

plural | who/what/which |

gun |

locative | where |

fim |

temporal | when |

xar |

manner | how |

nox |

reason | why |

rikag |

quantity | how many/much |

the interrogative pronouns can also be used in declarative sentences as indefinite pronouns, ie 'somebody', 'someone', etc.

these can recieve the negative prefix xi- to form negative indefinite pronouns.

verbs

verb phrase order

the overall order of the constituents of a verb phrase is:

- subject NP

- auxiliary: passive-negative-moods-deontic-stem-3p-causative-tense/aspect-converbs

- verb: stem-nonfinite

- indirect object NP

- direct object NP

- adverbs

- prep. phrases: preposition, noun phrase

- manner

- locative

- temporal

- other

auxiliary verbs

the majority of verbs in anachek require one of three auxiliary verb in order to convey grammatical information. the following tables show how all three auxiliary verbs conjugate for number, person, tense, and aspect.

the citation form for auxiliary verbs is the gerund.

| auxiliary verb 'ragati' | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | perfective | imperfective | ||||

| past | present | future | past | present | future | |

| 1S | wagape |

wagat |

wagaluk |

wagasape |

wagasa |

wagatak |

| 2S | ruwape |

ruwat |

ruwaluk |

ruwasape |

ruwasa |

ruwatak |

| 3S | rugape |

rugat |

rugaluk |

rugasape |

rugasa |

rugatak |

| 1P | wagupe |

wagut |

waguluk |

wagusape |

wagusa |

wagutak |

| 2P | ruwupe |

ruwut |

ruwuluk |

ruwusape |

ruwusa |

ruwutak |

| 3P | rugupe |

rugut |

ruguluk |

rugusape |

rugusa |

rugutak |

| auxiliary verb 'šimanki' | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | perfective | imperfective | ||||

| past | present | future | past | present | future | |

| 1S | wumape | wumak | wumaluk | wumasape | wumasa | wumakak |

| 2S | šimape | šimak | šimaluk | šimasape | šimasa | šimakak |

| 3S | gumape | gumak | gumaluk | gumasape | gumasa | gumakak |

| 1P | wumakupe | wumaku | wumakuluk | wumakusape | wumakusa | wumakusuk |

| 2P | šimakupe | šimaku | šimakuluk | šimakusape | šimakusa | šimakusuk |

| 3P | gumakupe | gumaku | gumakuluk | gumakusape | gumakusa | gumakusuk |

| auxiliary verb 'kanani' | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | perfective | imperfective | ||||

| past | present | future | past | present | future | |

| 1S | wanape | wana | wanaluk | wanasape | wanasa | wanasuk |

| 2S | qanape | qana | qanaluk | qanasape | qanasa | qanasuk |

| 3S | gunape | guna | gunaluk | gunasape | gunasa | gunasuk |

| 1P | wanupe | wanu | wanuluk | wanusape | wanusa | wanasuk |

| 2P | qanupe | qanu | qanuluk | qanusape | qanusa | qanusuk |

| 3P | gawupe | gawu | gawuluk | gawusape | gawusa | gawusuk |

simple verbs

a small, closed class of verbs can appear conjugated for tense, person, and perfectiveness without the need of auxiliary verbs. their citation form is also the gerund.

these verbs still take the normal compound forms to convey anything other than past/present/future perfective/imperfective and they conjugate like a normal compound verb in those cases.

auxiliary verbs also count as simple verbs; they take the same conjugations.

the following is the simple verb personal inflectional paradigm; because person and number are mostly shown through ablaut to and infixation or suffixation of the vowel u, several verbs that inherently contain the vowel u as part of their root create separate patterns of conjugation and consequently are able to only show a select number of person/number contrasts. simple verbs that inherently contain a 'u' in their root are called weak verbs. verbs with only one syllable are called short verbs.

| person/number | typical | left-leaning weak | right-leaning weak | double weak | short | short weak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1S | CVCVC | CuCVC | CVCuC | CuCuC | CVC | CuC |

| 2S | CuVCVC | CuVCuC | CuVC | |||

| 3S | CuCVC | CuCuC | CuC | |||

| 1P | CVCuC | CuCuC | CVCuC | CVCu | ||

| 2P | CVCVuC | CuCVuC | ||||

| 3P | CVCVCu | CuCVCu | CVCuCu | CuCuCu | CVCu |

here V stands for any non-'u' vowel (a, e, i, o), and C can stand for any number of any consonant; typically one or zero but the middle consonant is capable of representing a two-consonant cluster across syllables as with the verb šindub 'keep', which is a right-leaning weak verb.

also note that the terminology of weak and short verbs does not apply to compound verbs as they never conjugate for person and number.

the following are the simple verb tense/aspect suffixes:

| aspect | past tense | present tense | future tense |

|---|---|---|---|

| perfective | -pe | -∅ | -luk |

| imperfective -V | -sape | -sa | -suk |

| imperfective -C | -ape | -a | -ak |

the perfective aspect is used for finished actions or speaking of actions as a whole.

the imperfective aspect shows an unfinished action or currently true state.

compound verbs

the majority of verbs, which cannot be conjugated on their own, can express various moods and aspects with the addition of one of three auxiliary verbs. the main verb is in one of two non-finite forms and the auxiliary verb takes one of the simple verb conjugations. only the perfective or imperfective conjugations matter for the auxiliary verbs; tense suffixes function largely independently of the produced modal/aspectual meaning; for example, an interruptive configuration is the same whether the auxiliary verb is given the past, present, or future tense, except for the literal temporal location of the verb.

the following is a list of possible combinations and their meaning.

the perfective configuration is formed with the auxiliary ragati in the perfective aspect followed by the main verb in the participle.

the compound perfective functions the same as the simple perfective; finished actions or to speak of actions as a whole.

the progressive configuration is formed with the auxiliary šimanki in the imperfective aspect followed by the main verb in the gerund.

it is used for actions currently happening.

the imperfective configuration is formed with the auxiliary ragati in the imperfective aspect followed by the main verb in the gerund.

the compound imperfective functions the same as the simple imperfective; an unfinished action or currently true state.

the habitual configuration is formed with the auxiliary ragati in the imperfective aspect followed by the main verb in the participle.

it is used for actions that happen routinely and actions regarded to be true.

the experiential configuration is formed with the auxiliary šimanki in the perfective aspect followed by the main verb in the participle.

this is used to, from the speaker's knowledge, verify that the subject has done/experienced a specific action.

the dubitative configuration is formed with the auxiliary ragati in the perfective aspect followed by the main verb in the gerund.

it is used to show that the speaker doubts that the action happened.

the interruptive configuration is formed with the auxiliary šimanki in the imperfective aspect followed by the main verb in the participle.

this form is used to indicate actions that have recently been interrupted or forced to end in any way.

the conditional-permissive configuration is formed with the auxiliary kanani in the perfective aspect followed by the main verb in the gerund.

this form shows either that some action is dependent on some condition; similar to the usage of "would" in english conditionals, or whether or not the subject is permitted to carry out the action. the latter is often used as a soft or polite imperative.

note that whether the conditional or the permissive readings are meant is ambiguous but typically discernable from context.

the potential-abilitative configuration is formed with the auxiliary kanani in the imperfective aspect followed by the main verb in the gerund.

this configuration is used to indicate the possibility of a verb happening, or that a subject is capable of carrying out the action.

the optative configuration is formed with the auxiliary šimanki in the perfective aspect, with the deontic prefix to-, and followed by the main verb in the gerund.

this is used for expressing hopes and wishes.

the obligative configuration is formed with the auxiliary kanani in the imperfective aspect, with the deontic prefix to-, and followed by the main verb in the gerund.

it is used for actions that the speaker thinks are necessary to be brought about; similarly to "should" in english.

note that negating the obligative is ambiguous between "shouldn't" and "don't have to".

negation

verbs can be negated with the prefix xi(v)-. with compound verbs this only goes on the auxiliary verb.

anachek does not experience negative concord; that is, double negatives

moods

verbs can be marked for two moods: subjunctive and imperative.

the subjunctive mood, marked with the prefix nu- verbs that are in subordinate clauses. with compound verbs, this prefix is only used on the auxiliary verb.

the imperative mood, marked with na-, is used to denote an order given by the speaker. auxiliary verbs are not used with the imperatives, nor do verbs take any person, tense, or aspect marking whatsoever, with the exception of the copula that has a singular and plural imperative form.

it is important to note that since imperatives do not take any auxiliaries or other markings, the imperative form will override any expected form in other constructions such as conditionals

the imperative also encompasses hortative expressions, though these can be interchangable with obligative or potential-abilitative compound verbs with little difference in meaning

non-finite forms & converbs

there are two main non-finite forms alongside a set of four converbs.

the most common use case for the non-finite forms is to be applied to compound verbs to help show grammatical information in conjunction with auxiliary verbs as shown above.

additionally however, the gerund is used to nominalise verbs. it is formed with the suffix -ani. it can take the passive and the causative but not tenses nor aspects. the causative suffix comes before the gerund.

expressing subjects with the gerund uses the genitive; with the subject belonging to the verb. expressing objects is done by placing the object in the instrumental case.

the participle can be used to form modifiers of noun phrases from verbs. it is formed with the suffix -(V)n, with V echoing the last vowel in the word if it ends with a consonant. the participle can take the passive voice, but not tense, aspect, nor the causative.

converbs serve the purpose of creating adverbial clauses.

the imperfective converb is used to indicate that a verb is happening at the same time as another verb. it is marked with the suffix -afun.

the causal converb signifies a verb that happens as a consequence of another verb. it is shown with the suffix -apal.

the purposive converb marks an action as an intentional consequence of some other verb. it is marked using -awal.

the conditional converb is used for marking conditions for bringing about another verb. it is shown by -aka.

valency

verbs are typically labile; meaning they can change their transitivity as needed. this happens in a strictly accusative pattern.

another way of increasing transitivity is through the causative voice, marked by the suffix -uxu. with a causative verb, the causer is the subject, followed by the verb, then the causee actually performing the verb, and then continuing with typical word order. the causee remains nominative.

one way to decrease transitivity is with the passive voice, expressed with the prefix kan-. this demotes the subject and promotes the former object to become the new subject. the passive verb agrees in person and number with the new subject/former object

the demoted subject can be reintroduced to a passive verb as an oblique phrase with the ablative case.

furthermore, impersonal verbs can be expressed by having no subject but conjugating the verb in the third person singular anyways

reflexive constructions drop the subject if it is pronominal, and the object is occupied by the appropriate reflexive pronoun. reciprocal constructions are conflated with reflexive constructions.

syntax

constituent word order

though word order is somewhat free and ordered according to saliency, word order in anachek is normally subject-verb-object - SVO. indirect objects come between the verb and the direct object.

any element can be fronted to indicate topicalisation. this is accompanied with a change in intonation.

copula

copular constructions involve the verb kexani. it functions as a typical simple verb; it agrees in person and number with the subject, and takes tenses and aspects, the only two differences are that it is not inflected into the subjunctive, and that it has a plural imperative form. objects of copular constructions are still considered accusative; this only matters with pronouns as they are the only words that are inflected for the accusative.

| copula 'kexani' | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | perfective | imperfective | ||||

| past | present | future | past | present | future | |

| 1S | wepe | we | weluk | wexape | wexa | wexak |

| 2S | yepe | ye | yeluk | yexape | yexa | yexak |

| 3S | xepe | xe | xeluk | xexape | xexa | xexak |

| 1P | wupe | wu | wuluk | wuxape | wuxa | wuxak |

| 2P | yupe | yu | yuluk | yuxape | yuxa | yuxak |

| 3P | xupe | xu | xuluk | xuxape | xuxa | xuxak |

adverbs

words that are inherently adverbs constitute a small, closed class of words. to use a word, typically adjectives, as an adverb, the prefix su(s)- is added.

comparatives

comparatives are formed using the simple verb sanun 'to exceed', with the object of comparison functioning as its subject and the standard of comparison as its object. nominal objects of comparison are assumed to be compared on the basis of their quantity, and non-nominal objects must be nominalised in some way. the most common use case concerns adjectives, which do not undergo any morphological change on becoming nominalised, for instance. null/absolute comparatives that lack a standard of comparison are invalid and do not occur.

superlatives are formed simply by the addition of the quantifier nuces 'most' after the adjective.

questions

yes/no questions follow typical word order but end in the particle yu.

a yes/no question is answered by repeating the verb, negating it and changing the subject agreement if necessary. the auxiliary verb is also echoed alongside the main verb, though the main verb can be dropped in informal contexts.

interrogative questions follow typical word order and the interrogative word stays in place of the missing word. the particle yu is not used.

disjunctive questions also end with yu and follow the same order as yes/no questions. the particle tot goes between every choice.

pivot

anachek has an accusative pivot, meaning between two clauses connected together if the subject of the verbs of the two clauses are the same it can be left out of the second clause. the same is not possible if the object of the first clause is the subject of the second clause; it cannot be dropped.

if the shared NP is 2nd or 1st person singular or plural it can always be dropped, regardless of its syntactic roles, provided that the verb in the second clause can unambiguously mark it.

subordination

generally, a subordinate clause will start with some subordinating conjunction, usually a proximal class II adjectival demonstrative, and continue with standard word order, with the (auxiliary) verb given the subjunctive prefix.

the copula does not take the subjunctive prefix.

interrogative content clauses do not start with a conjunction. they follow standard interrogative question order, ie the same as declarative word order.

when converbs are used, the resulting clause will not have a subordinating conjunction and the verb is not marked with the subjunctive.

relative clauses always start with the interrogatives rik/rek/gut, agreeing with the head if it is class I, class II, or plural respectively, while leaving a gap in the relative clause where the shared noun would go.

topic & focus

as stated previously, topics are often placed at the beginning of sentences, and given the instrumental case in order to emphasise them.

the focus is typically unmarked, but is emphasised with a cleft sentence, taking the form:

focus NP, copula, pronominal determinative agreeing with focus, relative clause containing rest of sentence.

the order of the focus and the noun phrase containing the determiner and the relative clause are not fixed and can be switched.